Make Yourself A Better Engineer Through Systematic Daily Habits

When I was 10 years old I learned the power of daily habits by procrastinating for piano lessons.

I was supposed to practice for an hour a day between weekly lessons. Some weeks I’d diligently do my daily practice, and other weeks I’d procrastinate, trying to fit six hours of practice into the one or two days before my lesson.

I observed that even when I put the same amount of clock time into practicing, the results were significantly better when spread out over daily intervals.

When I got older, I learned there’s research showing that muscle memory, cognitive functions, and other skills improve with periods of rest (especially sleep), allowing for new information to be processed and absorbed.

I’m not sure who came up with this phrase, but I’ve found it holds true:

What you do a little of every day matters more than what you do a lot of every once in a while.

Below are some of the habits I’ve developed to build my skills as an engineer:

Clearly separate “work” from “breaks”

The Pomodoro technique is great for this. It’s important to separate work time from break time, otherwise they blur together. With a clear separation and a known break around the corner, it’s easier to focus intently on the task at hand.

Set goals before starting each day

Daily goals prioritize what’s important and what isn’t. I write these out in the morning before I open my computer.

This daily list becomes a touchstone I flip back and refer to numerous times throughout the day. It keeps me on task and tunes out distractions.

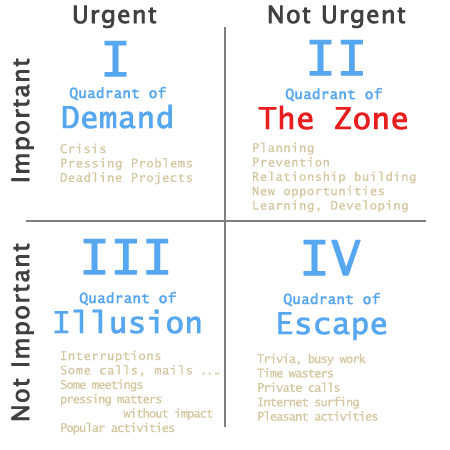

I prioritize my tasks using Stephen Covey’s time management matrix, which helps me distill what matters:

The goal is to maximize the time I spend doing high importance, low urgency work, aka “The Zone.”

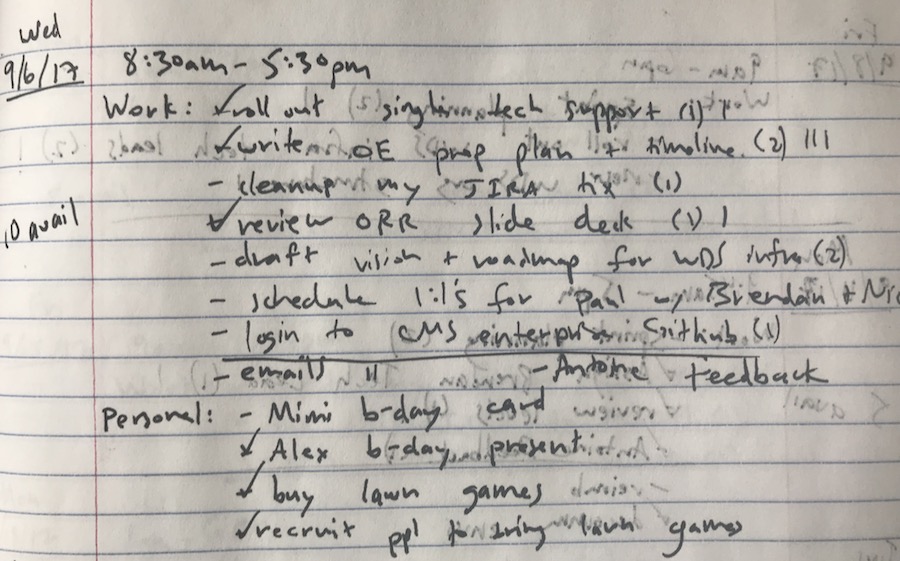

For the past few years I’ve been writing out my daily goals with a pen in a journal.

Here’s an example of how I currently track my goals for one day:

The specific format I’ve used has evolved over time, but the core elements I try to measure are:

- prioritized list of tasks for the day (both work & personal)

- time estimate for how long each task should take (the parentheses at the end of the task denote an estimate measured in pomodoros. e.g. “(2)”)

- how much time I have available outside of meetings to do work (measured in pomodoros. e.g. “10 avail”)

- specify what I hope to complete within the day vs stretch goals (e.g. the horizontal line separates realistic goal from stretch goal)

- mark tasks completed that day

- how long I actually spent on that particular task (measured in tick marks)

- the time I started and ended my day (this helps me identify trends of overworking)

Take regular breaks

I can’t even count the number of times I’ve had a key insight because I took a break. Hard problems can be like chinese finger traps: thinking less hard can get you unstuck faster. Taking a walk around the block or getting a good night’s rest often reveals the solution.

Regular breaks also help you stay on task and avoid rabbit holes. When returning from a break, you naturally re-evaluate the problem you’re working on, and oftentimes find you were on an irrelevant tangent!

Use early mornings for focused personal time

Some people prefer late nights, but personally I find I have competing social obligations or am too tired to effectively focus on personal projects at the end of the day. I’m always fresh and focused in the morning, which allows me to build a consistent daily routine. I also love this quote, which we know must be true because it rhymes:

Early to bed and early to rise makes a man healthy, wealthy and wise. - Benjamin Franklin

Currently I spend 7am-9am each morning before work on personal projects (like this blog!) and developing my engineering skills (like teaching myself Terraform and Docker). Because I’m a masochist, I’m now thinking of expanding this to 5:30am-9am.

Identify your distractions and block them out

For me, the biggest sources of distraction at work tend to be:

- Slack (and other instant messengers)

- Online articles (usually shared by my coworkers in Slack)

I use Inbox When Ready to stop myself from spending time on low value emails. I set Slack to “do not disturb” when I need to focus and minimize the application window to keep myself from reflexively tabbing over. I use Instapaper to save articles for reading later, outside of work hours.

There are productivity tools out there to manage all sorts of internet distractions you might face.

As I mentioned above, explicitly listing your goals for the day can also be a great tool for blocking distractions. It serves as a clear reminder for highest value use of your time.

Verbalize your thinking when stuck

Some people use a rubber duck. Some people are too self-conscious to talk to a duck in the middle of an office or coffee shop. :p

I write out my questions, hypotheses and observations as if I were to ask someone else on the team. 70% of the time I answer my own question just by laying out my thinking. If I’m still stumped, I can share what I wrote down with others on the team!

Invest in productivity tools

Here are some I use:

- Spectacle - resizes application windows with hotkeys

- ClipMenu - clipboard manager

- Dash - snippet manager

- 1Password - password manager

- Instapaper - saves articles for later

- Inbox When Ready - hides your inbox by default

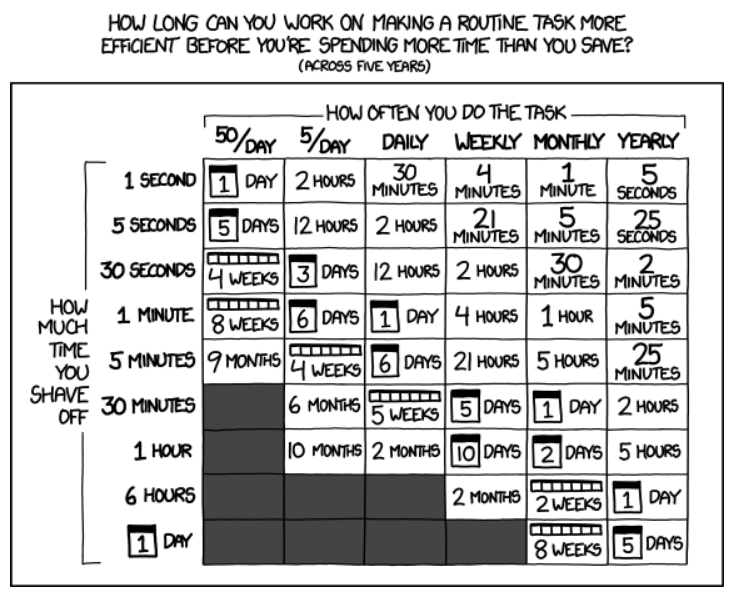

There are lots of other tools out there, so experiment! My general rule about whether to adopt a productivity tool is whether it simplifies a task I do 20+ times per day. Anything less and it’s usually not worth the setup, learning curve and hotkey memorization.

This xkcd comic gives a much more nuanced evaluation framework:

Learn hotkeys for everything

Clicking is slow. Typing is fast. Shaving off a few seconds for something you do tens or hundreds of times a day will make you more effective over the long haul.

One of my friends who works in investment banking told me how interns at his firm were given keyboards but no mice, forcing them to learn how to use excel with nothing but hotkeys. Investing a few painful weeks learning hotkeys surely makes a huge difference in productivity over the course of a career.

Write tech specs

Lay out your thinking before you start coding. Identify the files you need to change, the functions you need to modify, the database fields you need to access, the testing steps required to validate the change, etc.

The earlier you can identify mistaken assumptions or dependencies, the quicker you can arrive at a correct solution. It doesn’t have to be elaborate or prescriptive—a few bullet points or diagrams on a sticky note can often suffice for smaller problems.

For larger problems, it’s always worth the time to write out a detailed page or two to spec out the solution.

Constantly re-evaluate and modify your habits

Life is fluid. As your projects change, your life changes, your role changes, you’ll need to modify and re-adapt yourself and your habits. I typically try out any new habit for 2-3 weeks before evaluating its efficacy.

Conclusion

No one is innately born a great engineer. Every skill is learned. If you put in the hours, you will develop the skill.

If you want to be great at something, invest in your daily habits.